Karma Automated source code defect identification method

|=-----------------------------------------------------------------------=| |=----=[ Karma: Automated source code defect identification method ]=----=| |=-------------------------=[ by cipher.org.uk ]=------------------------=| |=-----------------------------------------------------------------------=| --[ Table of contents Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1.1 Problem to solve 1.2 Solution 2. Learning a language 2.1 Naïve Bayes classifier and source code analysis 2.2 The tool 2.3 Context based training 3. Analysing source code 3.1 Defect detection 3.2 Features 4. Works cited and bibliography

1. Introduction

Source code and binary defect inspection have become essential process of many, related to software development and software analysis. It is critical to identify defects (security, performance etc) within their software prior or after a release.

1.1 Problem to solveMost source code analysers are able to point to specific issues using "hard-coded" knowledge either based on strings or AST (or other intermediate representations) using rulesets and they are tightly connected to specific languages. Even though this could be successful, it is limited to:

- The number of supporting rules, languages etc

- Requires an expert for each programming language to be able and create the rulesets or lists respectively

- All string lists and rulesets are subjective to their author's knowledge, experience and perspective when assembling them, without taking into account, prior general and non-subjective knowledge.

In addition, they tend to direct the reviewer's focus as they provide vulnerability risk levels, which is good if the reviewer is not interested in looking at the source code in depth but instead producing a semi/automated list of issues.

The method described in this text provides:- A way of analysing source code of any language

- Visual assistance of areas of interest in every file (heatmap)

1.2 Solution

The main objective is to create a zero-knowledge source code analyser, able to point to any 'interesting pieces' of code within any language and context. Instead of creating a collection (e.g bugle, most source code analysis tools including AST based) of potentially dangerous strings or rulesets, we train a classifier do it for us very quickly.

Classify: “ … arrange (a group) in classes according to shared characteristics... assign to a particular class or category…”(Oxford Dictionary)

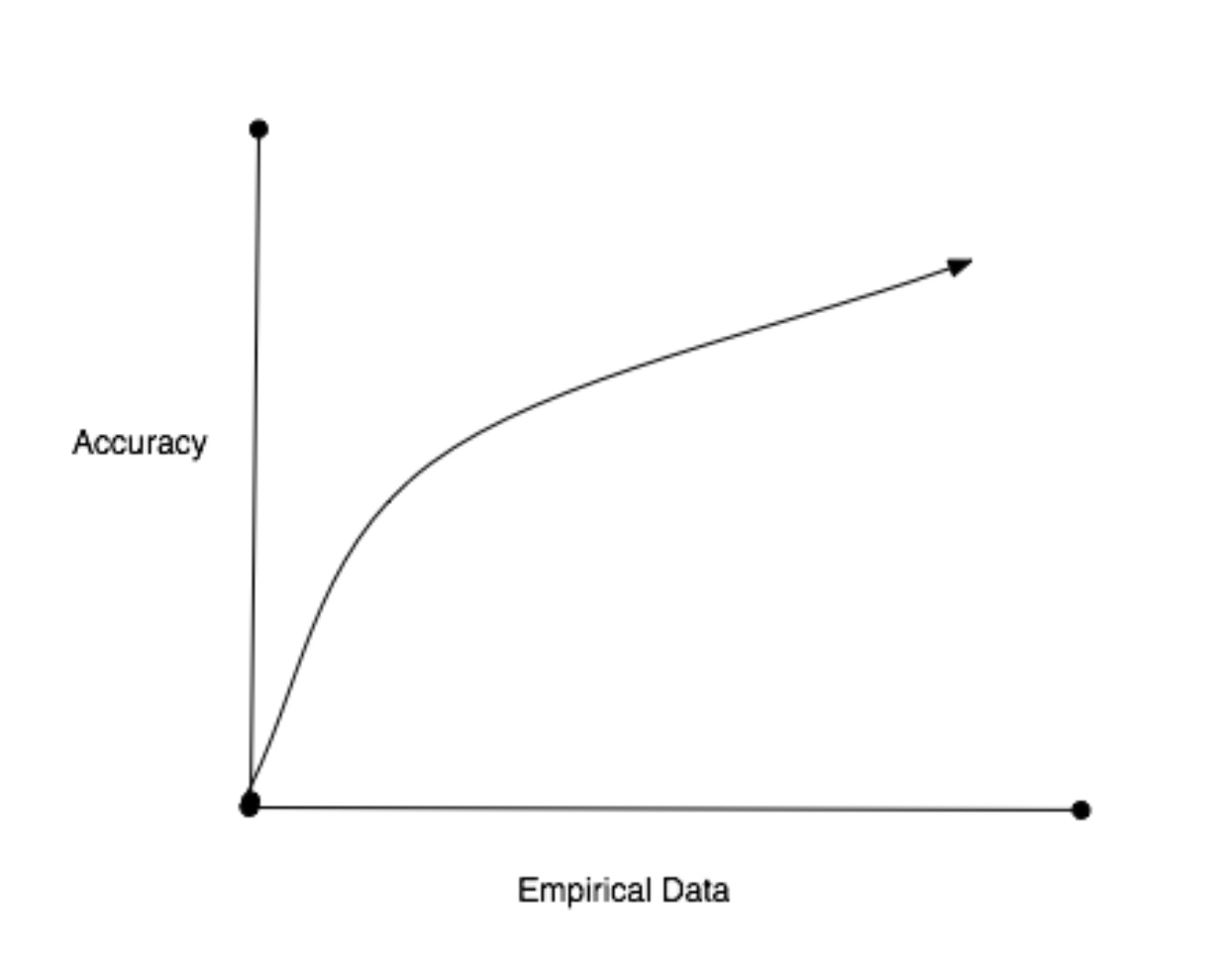

Data classification, a sub-discipline of machine learning (Webb) (Bishop) (MacKay) can be used to assist with the categorization of the under scrutiny data. However to achieve this, we need to provide empirical data to the classifier. We need to supply a large number of problematic code snippets or bugs for the classifier to acquire the required knowledge. A way to do it is using software patches.

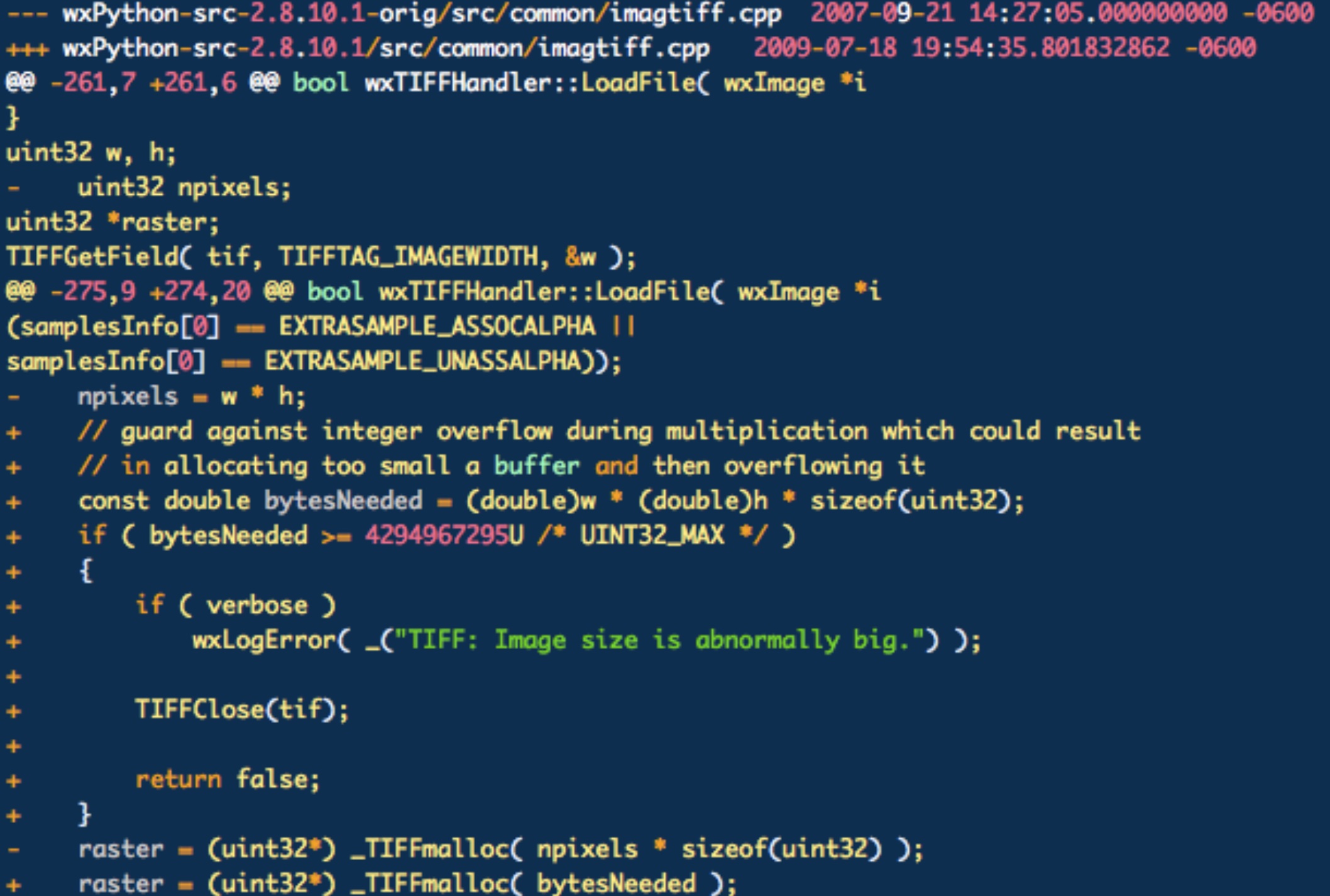

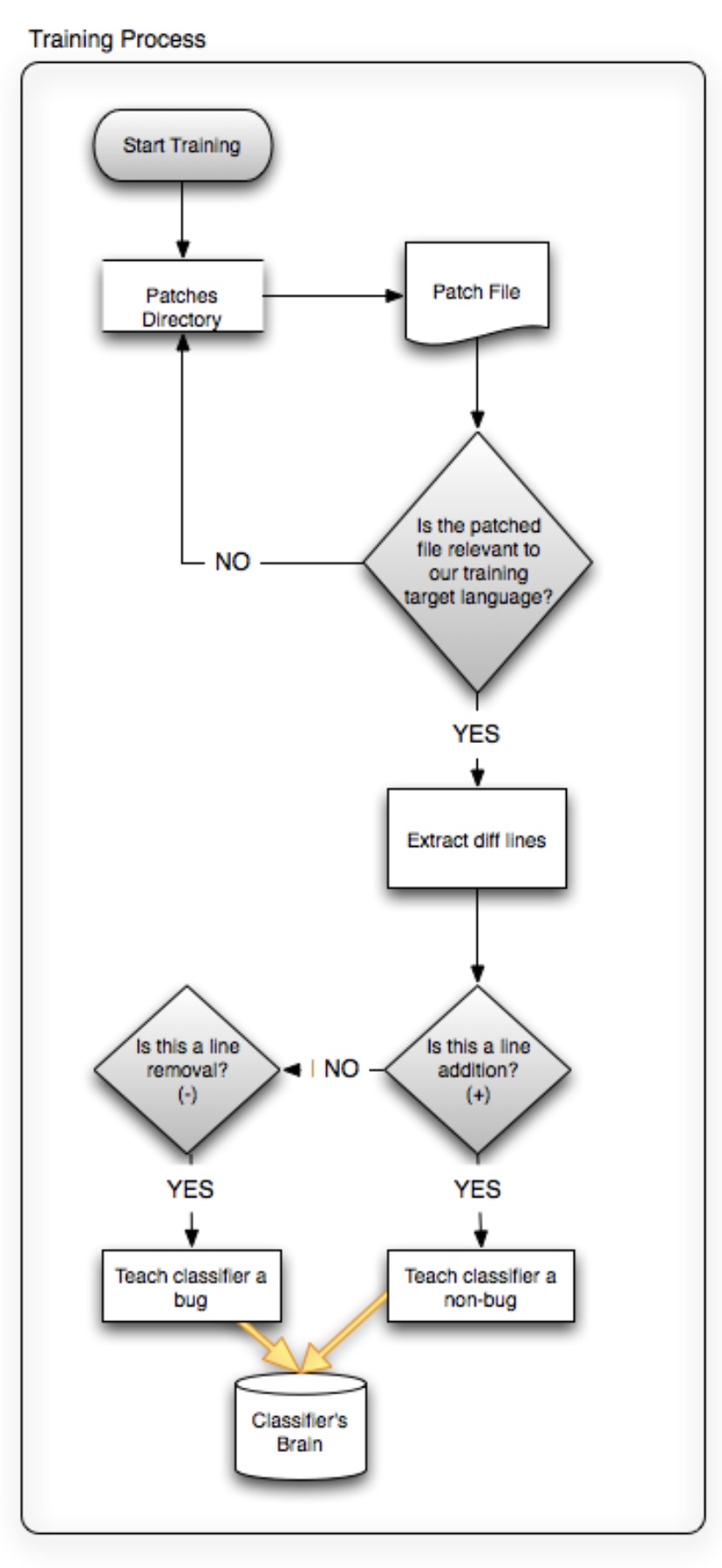

As we can see above, it is very clear how we can train a classifier using it. Lines with “-“ are lines which are going to be removed (therefore defects) and lines with “+” are lines that are added to the code (corrections). It needs to be noted that we make assumptions that added lines are correct (which is not always the case), however having a large enough patch collection, these anomalies should decrease.

2. Learning a language 2.1 Naïve Bayes Classifier and Source Code Analysis

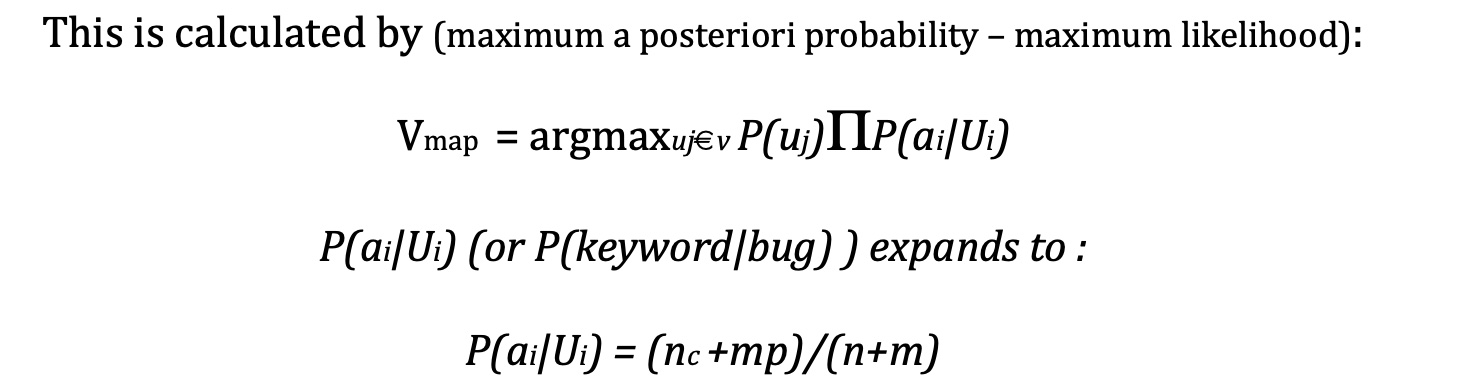

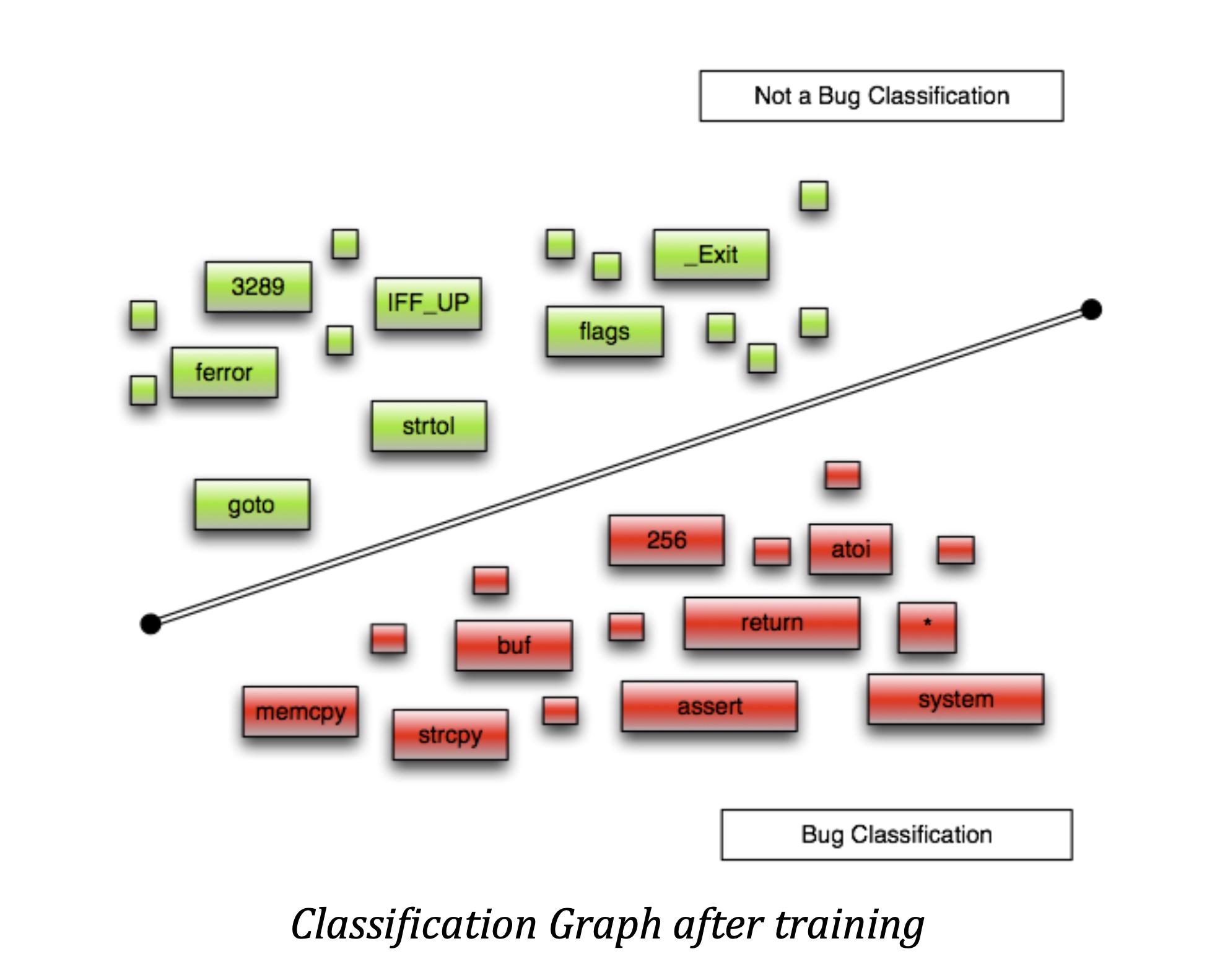

To understand a little bit more how this actually works, I am going to give a very brief example on how the classification happens during ‘training’ and how the code defect confidence is calculated.

Naive Bayes algorithm is a simplistic ,yet powerful, classification algorithm based on the Bayesian Theorem (Bayes & Price, 1763). During the training phase what essentially happens is we build a database of prior probabilities (aka prior knowledge – in our case patches). So we calculate the probability associated with an object to be a classified as a defect or not defect.

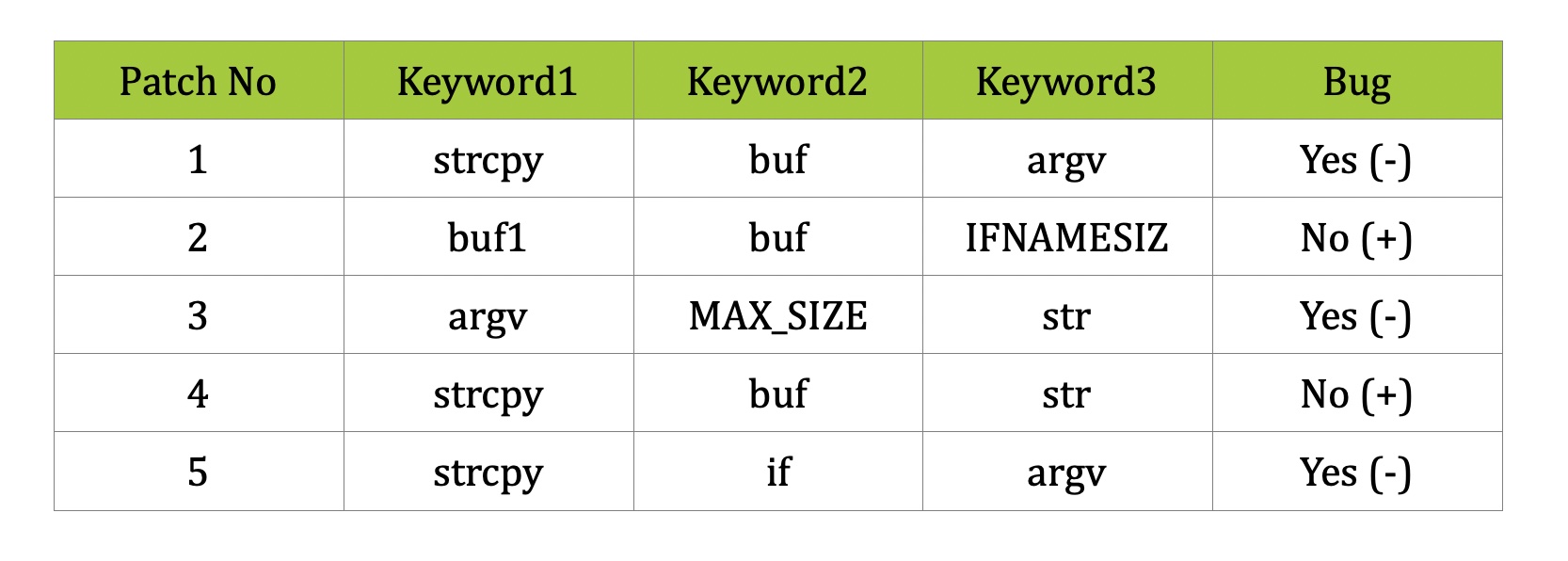

Lets assume that we have our training data (shown in the table below) which we acquired using our patches collection:

strcpy(buf,argv[1]);Assumptions for this example:

- 3 parameters - Keyword1-3

- 3 possible attribute values per parameter i.e. Keyword1 [strcpy, buf, argv]

- For simplicity, special characters and numbers are not calculated

A Naïve-Bayes classifier chooses the most probable classification when supplied the attribute values a1, a2, a3….an. In our case ai is keywords i.e. strcpy, buf etc.

- n is the number of times for which the current classification belongs to a category

- nc is the number of times for which the current classification belongs to a category for a specific parameter

- p is a prior estimation of P(keyword|bug)

- m is a constant, determines the weight to the observed data , essentially it increases n . In our case we pick a random value 2 for all data

Going back to the source code line we want to classify and after removing all special characters

strcpy buf argv

Now we want to calculate P(strcpy|yes) , P(buf|yes), P(argv|yes),P(1|yes) and the same for |no

I am going to explain only the first of these and hopefully the rest will be obvious:

P(strcpy|yes) = (nc +mp)/(n+m) n = 3 (3 instances where we positively have a bug within the training data - patches) nc= 2 (strcpy was in 2 of them) p = 1/3 (1/possible number of values for this attribute) m = 2 (constant – should be the same in all the calculations)So P(strcpy|yes) = (2+(2*0.3))/(3+2) = 0.52 and the rest are

P(buf|yes) =0.32, P(argv|yes) = 0.52 We do the same for the classification ‘no’ : P(strcpy|no) = (1+(2*0.3))/(2+2) = 0.4 , P(buf|no) = 0.65 , P(argv|no) = 0.15 Finally we calculate P(yes) and P(no) as required by Vmap P(yes) =0.6 and P(no) = 0.4 So the maximum likelihood of this line being a bug is : Bug = P(yes)P(strcpy|yes) P(buf|yes) P(argv|yes) = 0.6 * 0.52 * 0.32 * 0.52 = 0.0519168 And the maximum likelihood of ths line not being a bug is : NotBug = P(yes)P(strcpy|yes) P(buf|yes) P(argv|yes) = 0.4*0.4*0.65*0.15 = 0.0156

Clearly Bug > NotBug and therefore, there is high possibility that this line is a bug

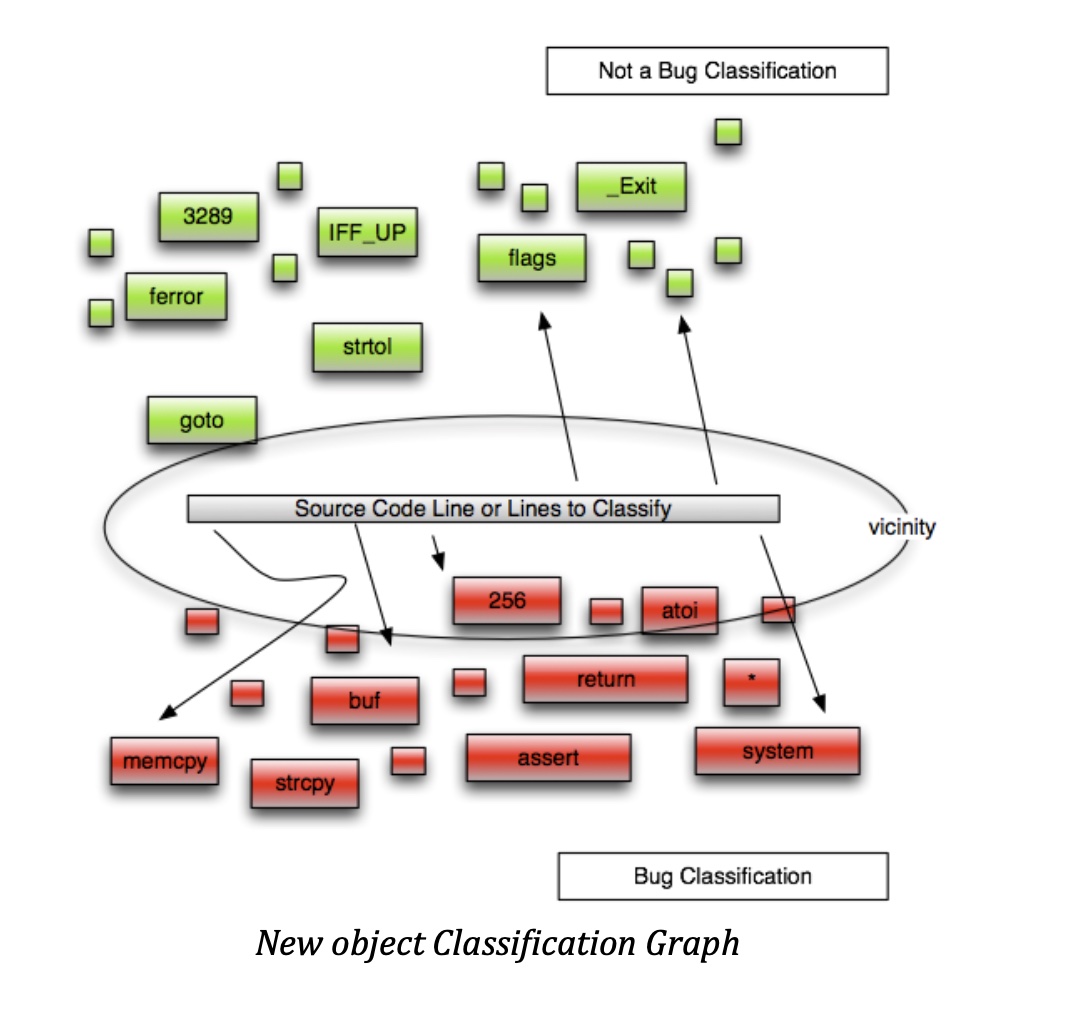

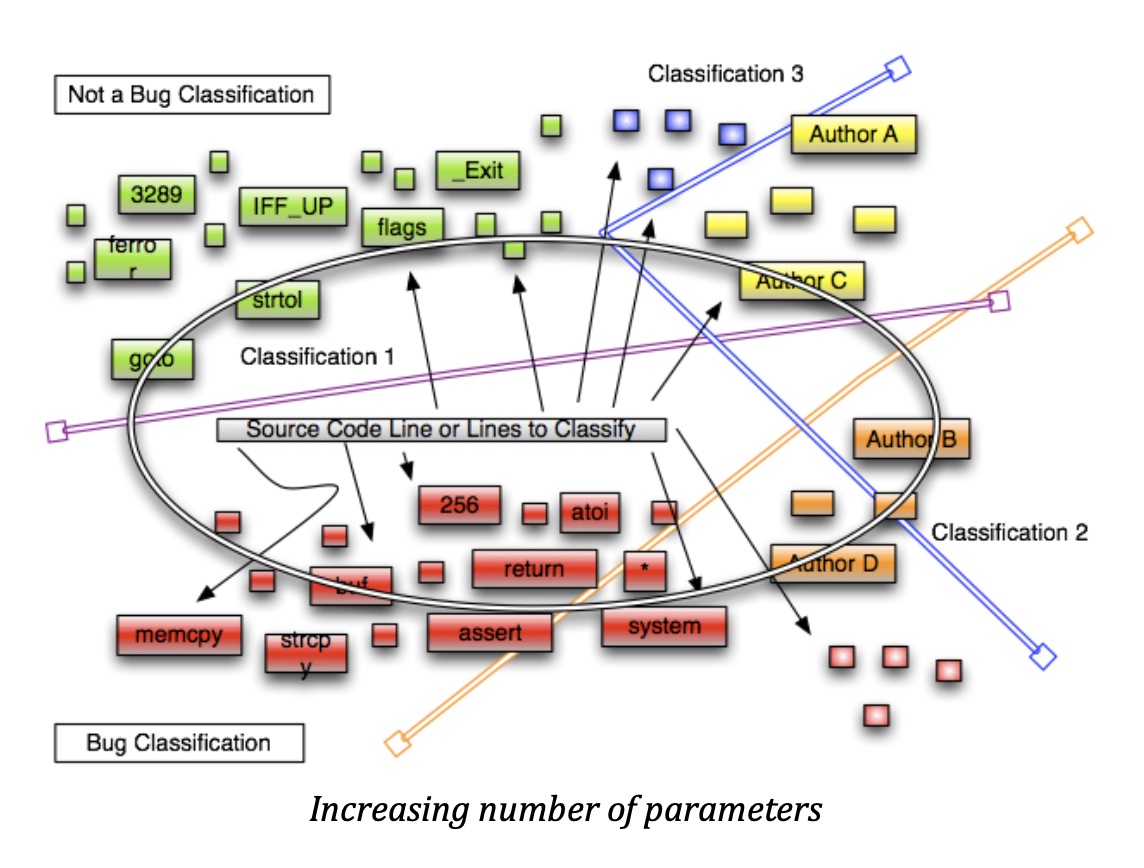

Note that this method can be tailored to very specific contexts. For example here we applying the algorithm on keywords acting as parameters, however we can do some more adjustments.

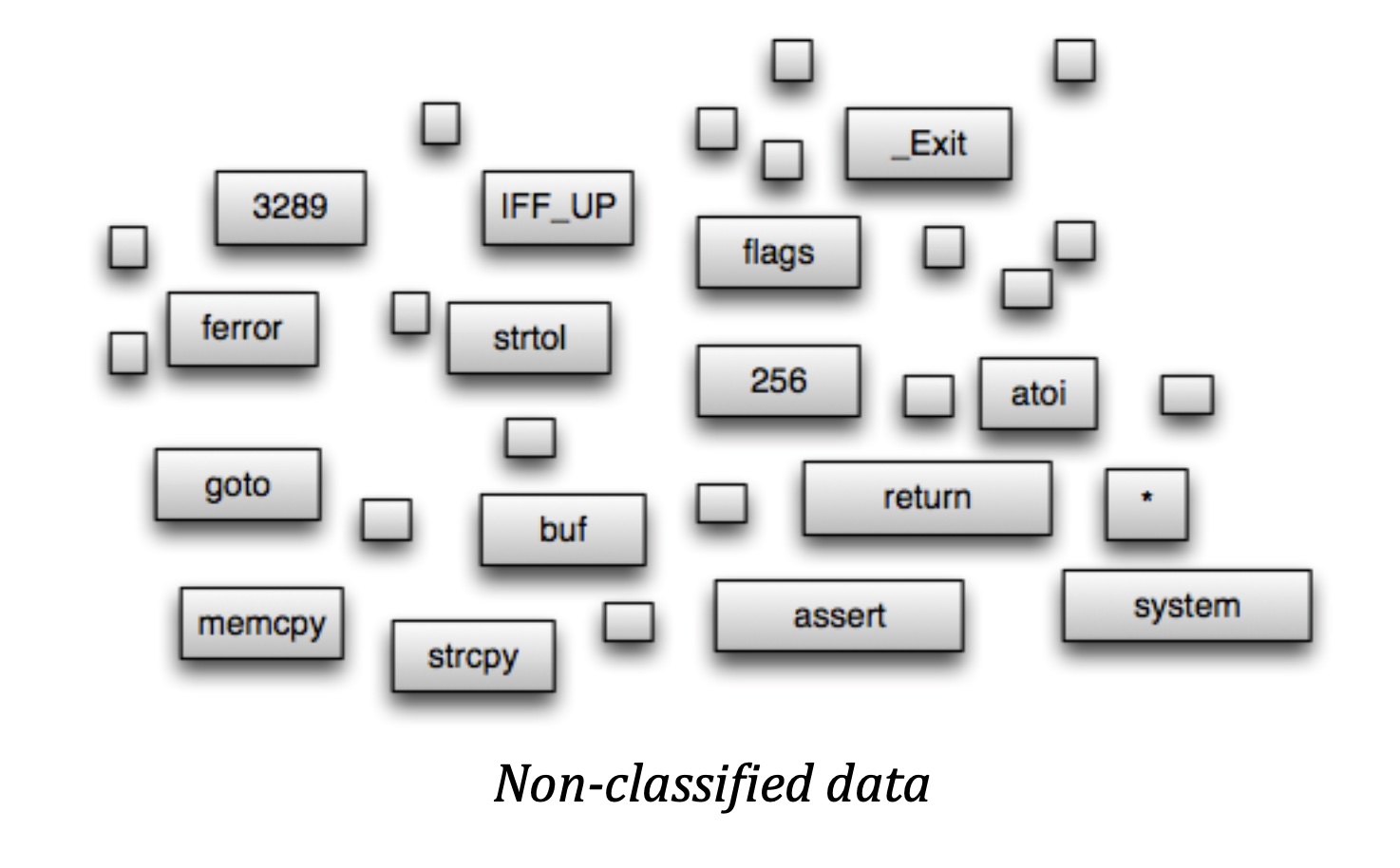

We could for example train the classifier using only a language’s tokens and known functions which can be good in abstracting the knowledge (however that wont catch interesting numbers such as 256, 1024 etc or variables such as buf etc). Also it can be applied to intermediate source code representations such AST in combination with syntax idiosyncrasies.

Additionally, by introducing parameters such us, developer, licensing (?), cyclomatic complexity (and other metrics) , file extensions for the same language (i.e. h or c for the C language) , comment ratios etc we can create a very high level of accuracy.

Even though it looks cluttered and a bit complicated, Naïve Bayes and most other classifiers can handle it and produce very good results. Note that this classifier makes some very strong independence assumptions (hence naïve), which means that all calculated probabilities are contributing to the final decision without affecting the final calculated probabilities of each other.

2.2 The tool

This text introduces Karma an implementation of a decision-making engine, based on the probabilistic classification provided by the Bayesian theorem. Here we are going to use a NAÏVE-BAYES classifier, however any other classifier can be used such as TREE AUGMENTED NAÏVE-BAYES, BN AUGMENTED NAÏVE-BAYES, Averaged One-Dependence Estimators or other non BAYES classifiers. (An Empirical Comparison of Supervised Learning Algorithms)

Disclaimer the tool Karma and it's predecessor ParmaHam are private since 2007 and 2010 respectively the source code is provided for Karma which is the latest iteration of the tool and it compiles with the latest Netbeans along with their binaries (pre-compiled versions) and can be found at the bottom of the paper. There are plenty of bugs so it will be much appreciated if you are developer or can develop you are very welcome to provide fixes here. The code is released under the Apache license

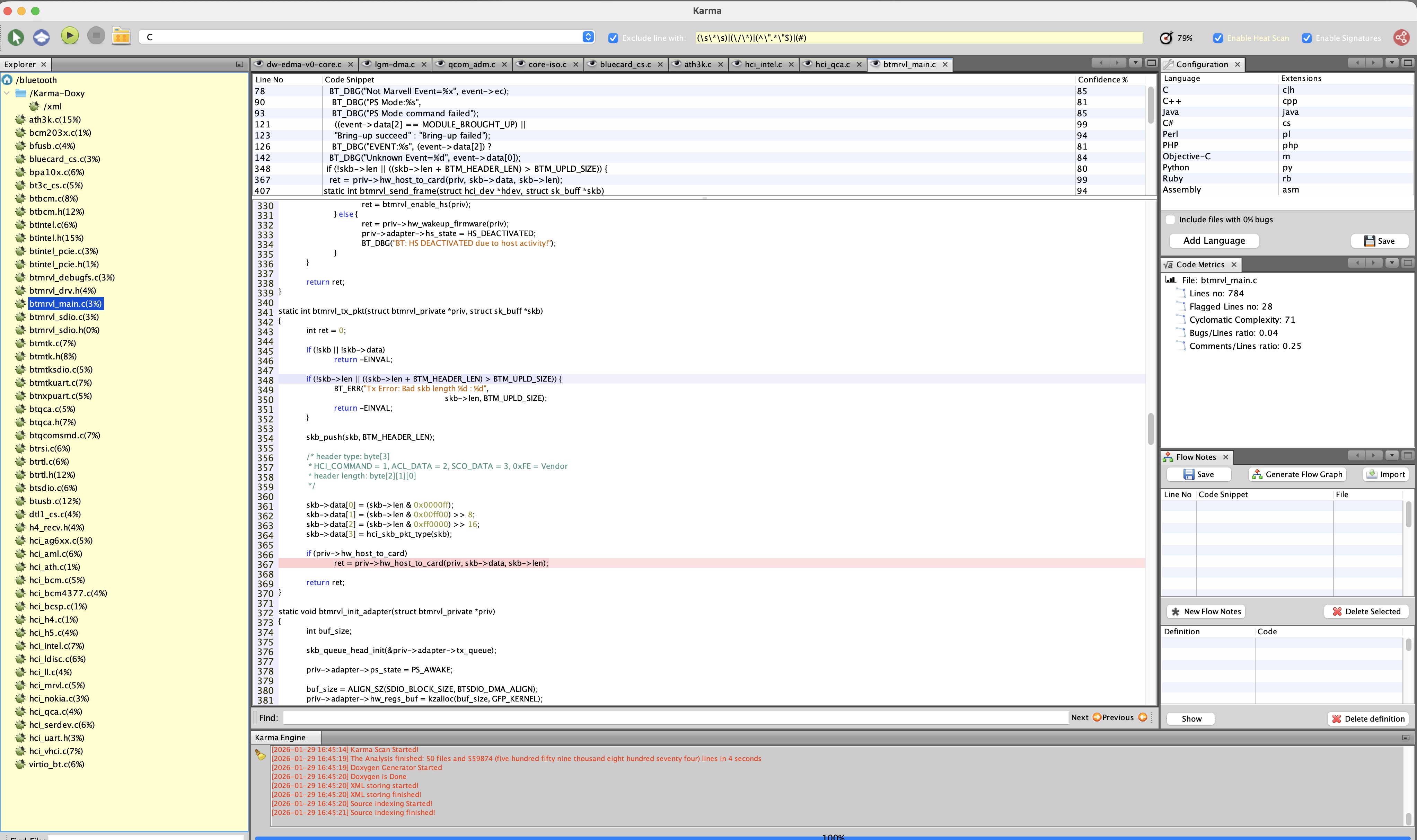

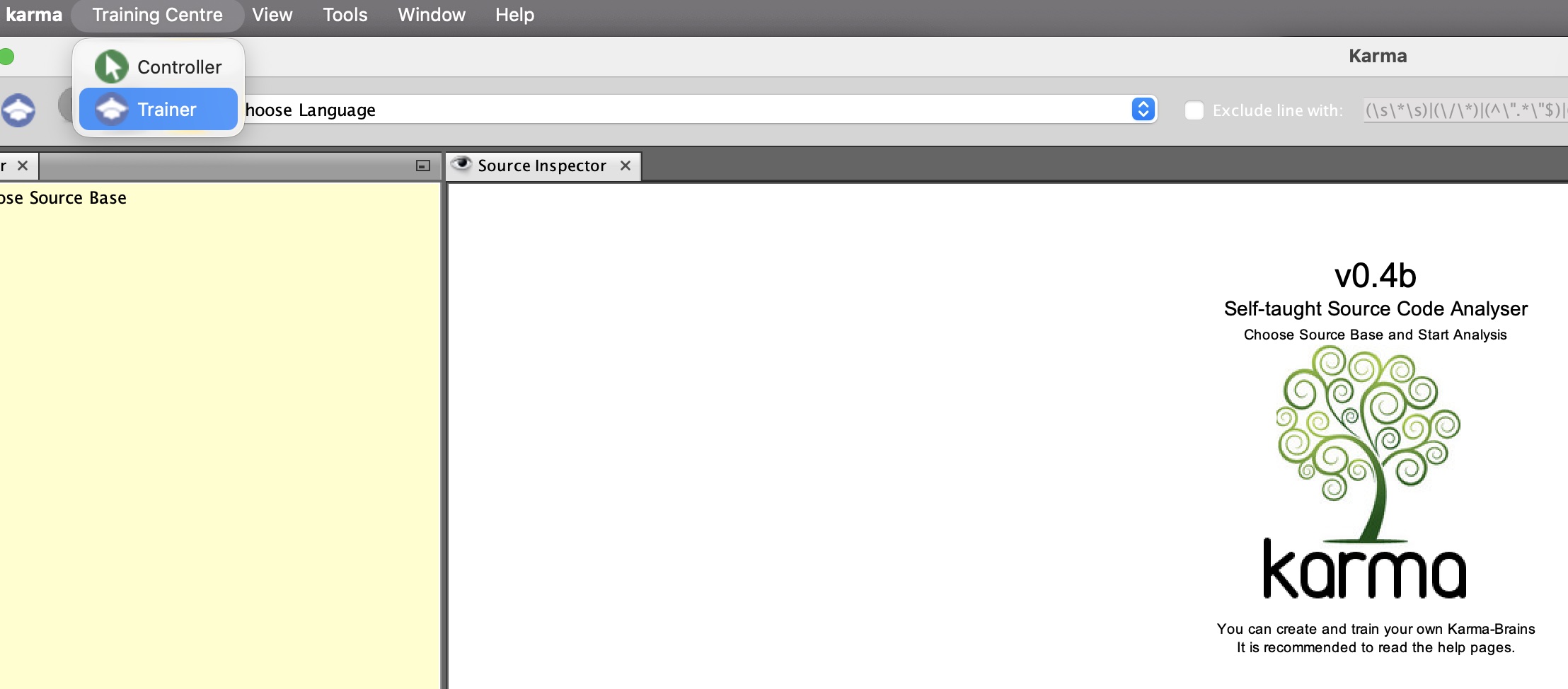

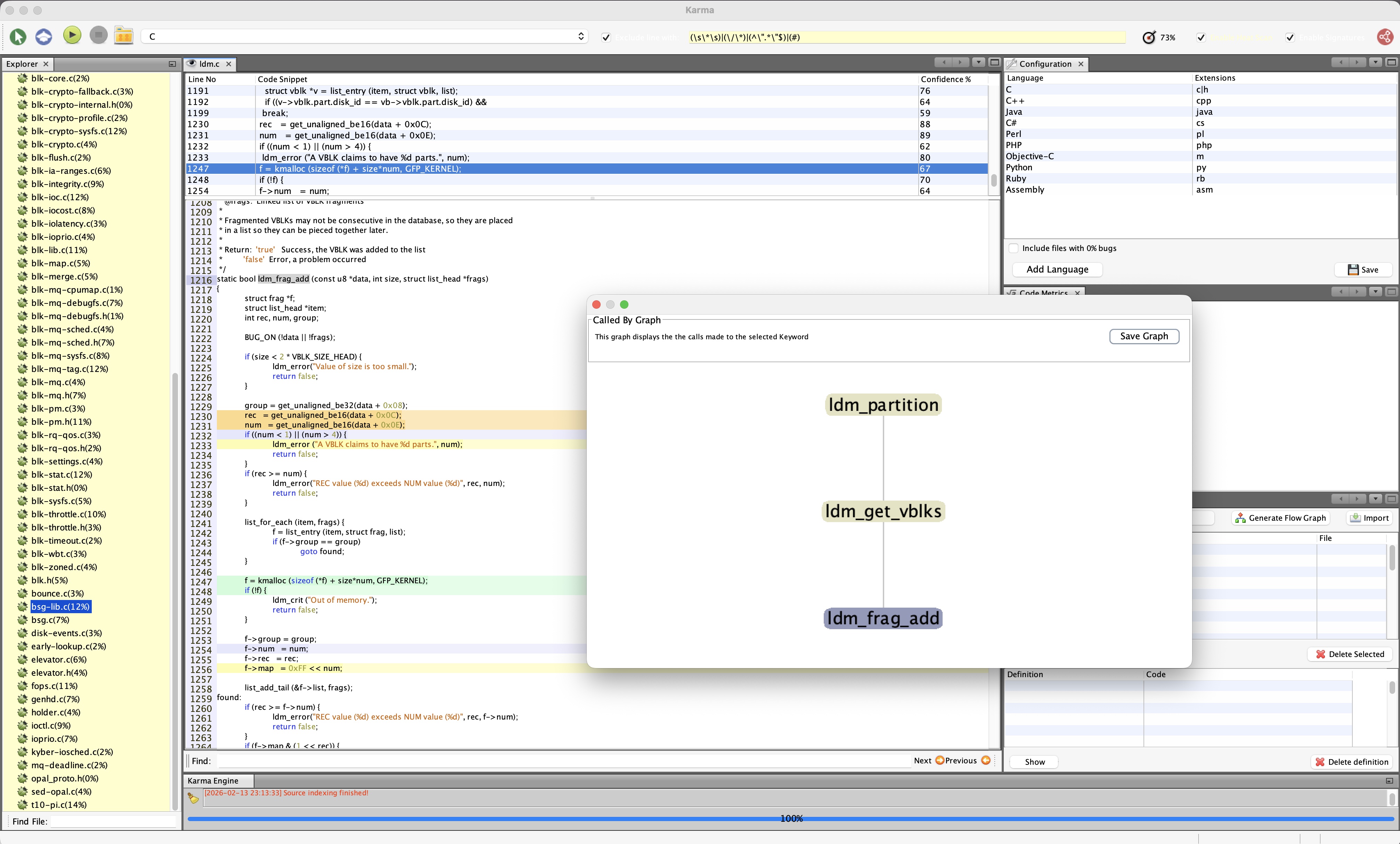

Below a screenshot from Karma

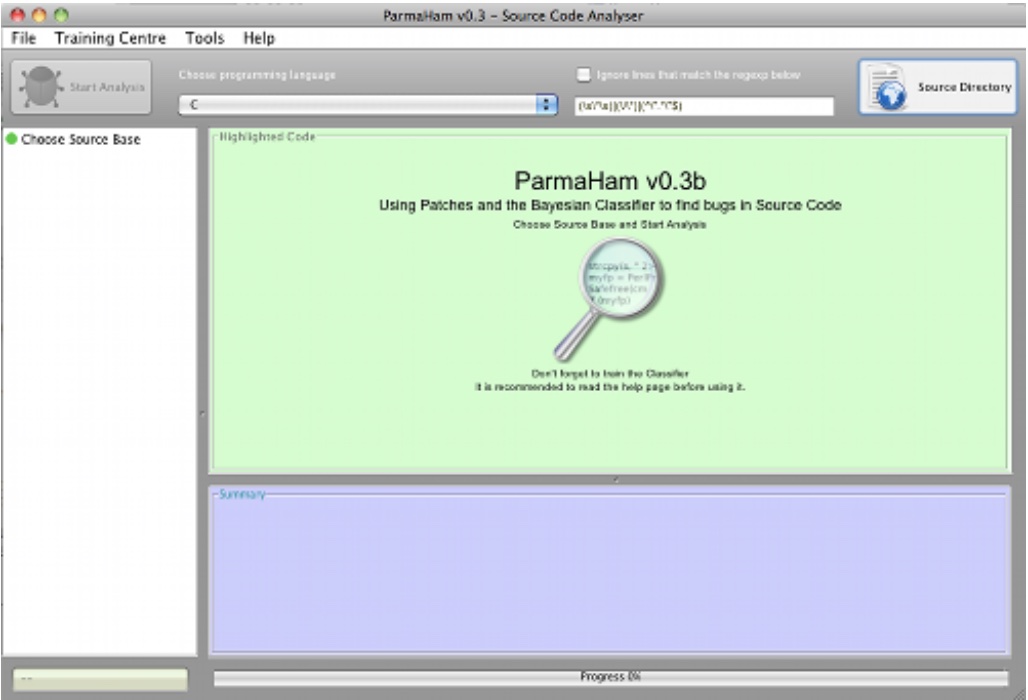

and a less advanced version ParmaHam for historical reasons below

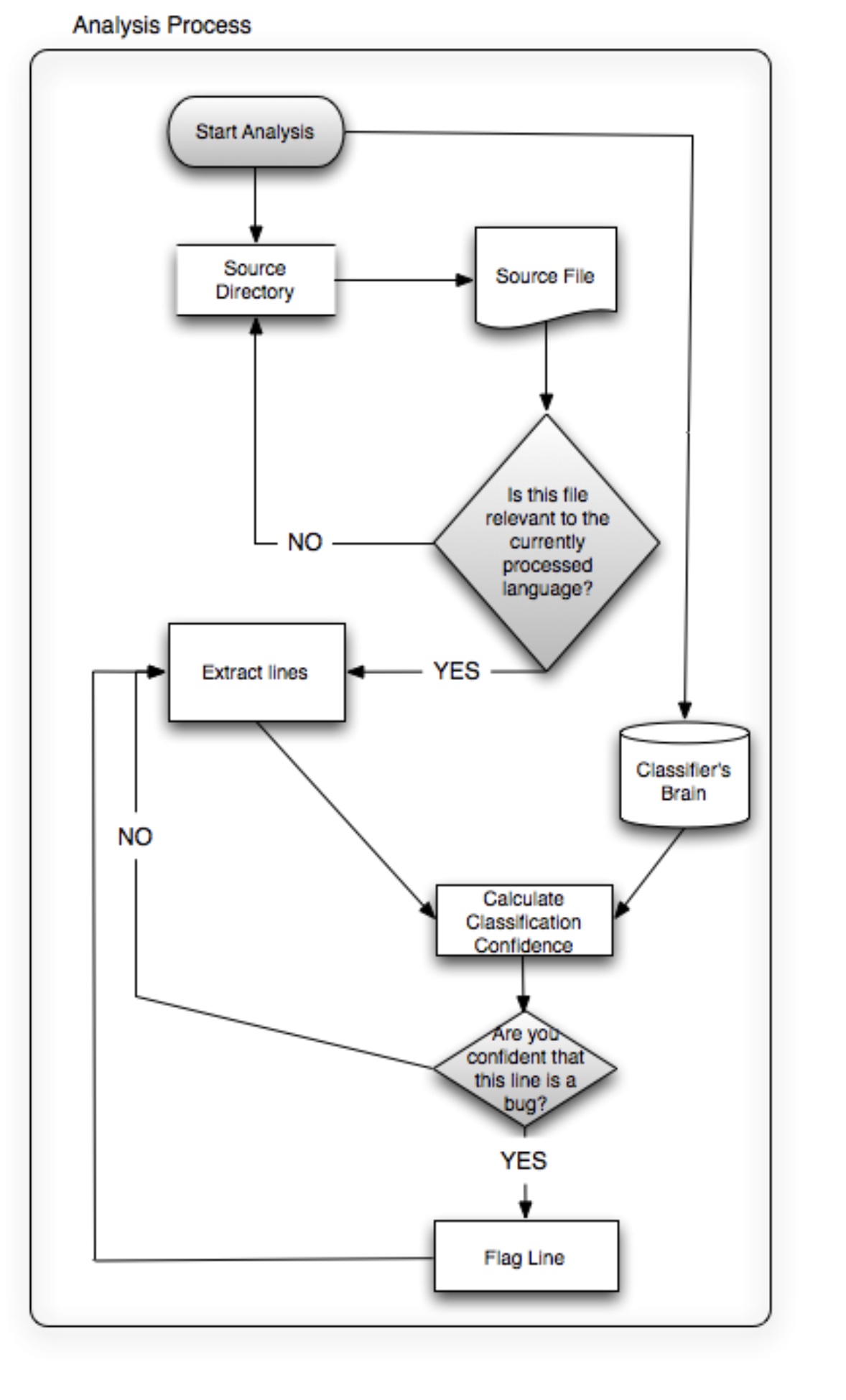

Using our collection of patches as our empirical knowledge, and following the method described earlier, we teach the classifier to recognise what is a bug (-) and what is not (+) for a specific language (---). The flowchart below illustrates the steps taken by Karma during this process.

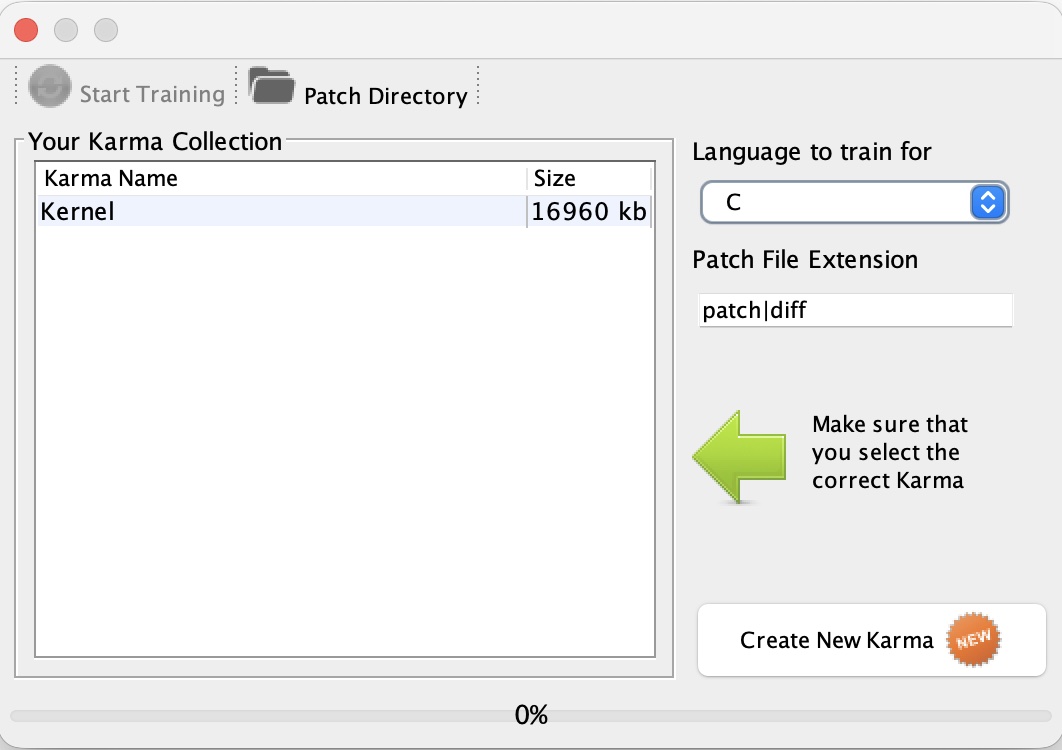

The process above is represented by the 'Trainer' dialog (see below) within the 'Training Centre':

What we need to provide to the 'Trainer' is:

- A directory with patches to learn from

- A language to train for

- What patch file extension we are looking for (i.e. diff, patch etc)

When all the info is in place, we 'Start Training' and the currently selected Knowledge DB is used to store all the acquired knowledge. You can choose the currently active Knowledge DB at 'Training Centre'.

2.3 Context based training

To achieve high accuracy in our results, we have to train our classifier in a specific context.

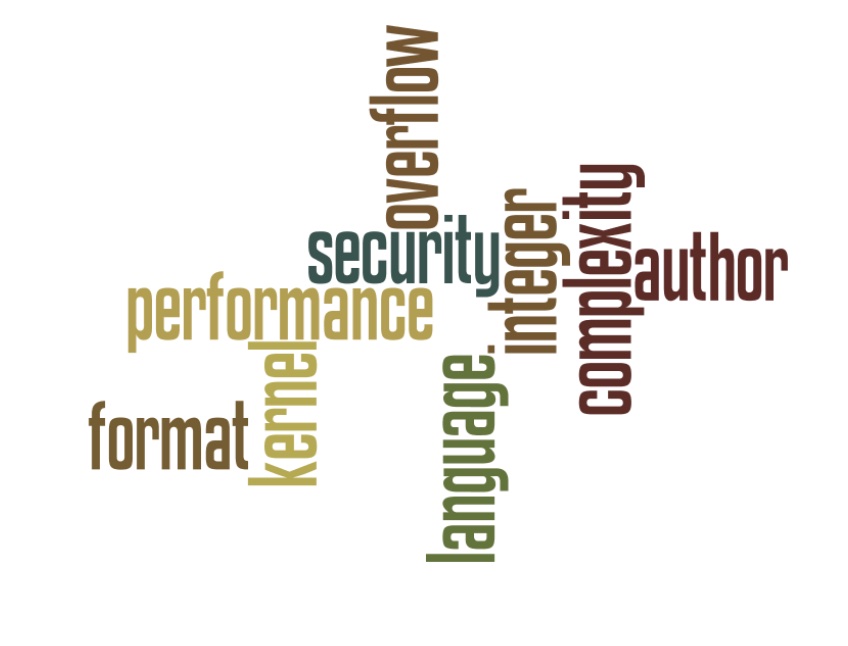

For example, if we are looking for security bugs, we have to train our classifier using security patches. Also if we are looking to find bugs in a specific environment, which may slightly differ like, let's say, kernel code, it would be a really good idea to train the classifier in kernel patches with security context. Also if we are looking within a specific bug category, such as integer overflows etc. we can train the classifier with these bugs.

Generally, closed source/commercial projects have better categorisation on different types of patches, so software houses may create more accurate classifiers, however many open source projects do that as well, so we can use them as a trainer for our classifier.

3. Analysing source code 3.1 Defect Detection

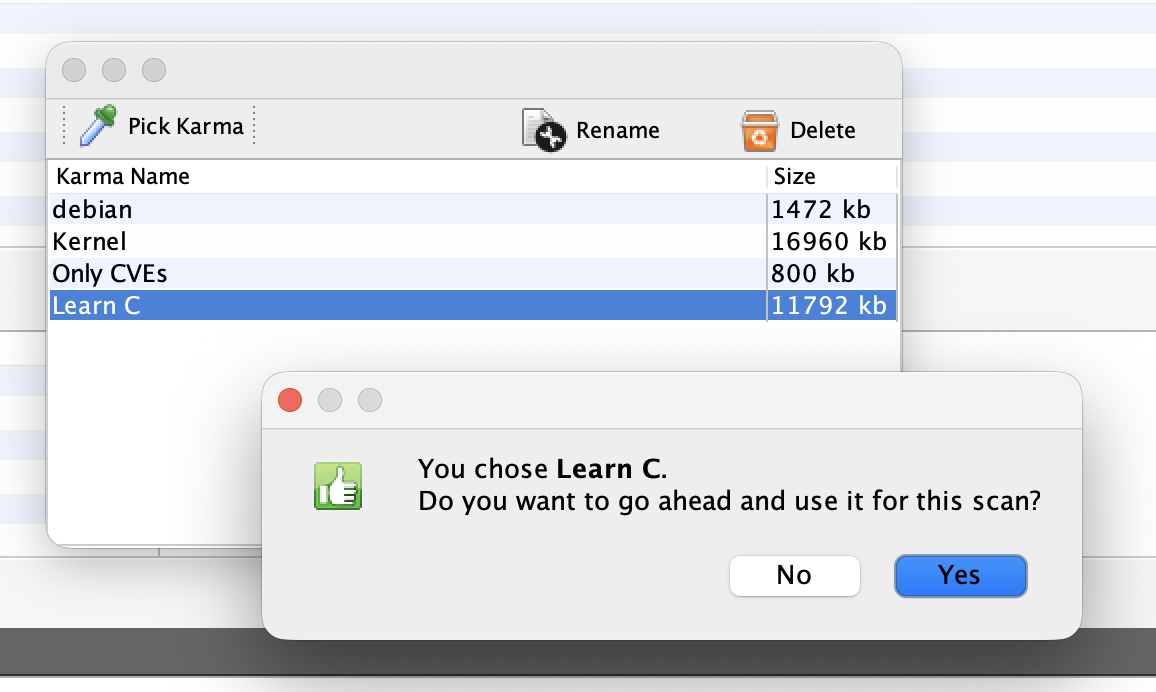

At this stage, we should have our classifier ready to analyse source code and potentially find areas that relate to past-knowledge as it has been acquired during the training phase. First we choose the Karma from the menu:

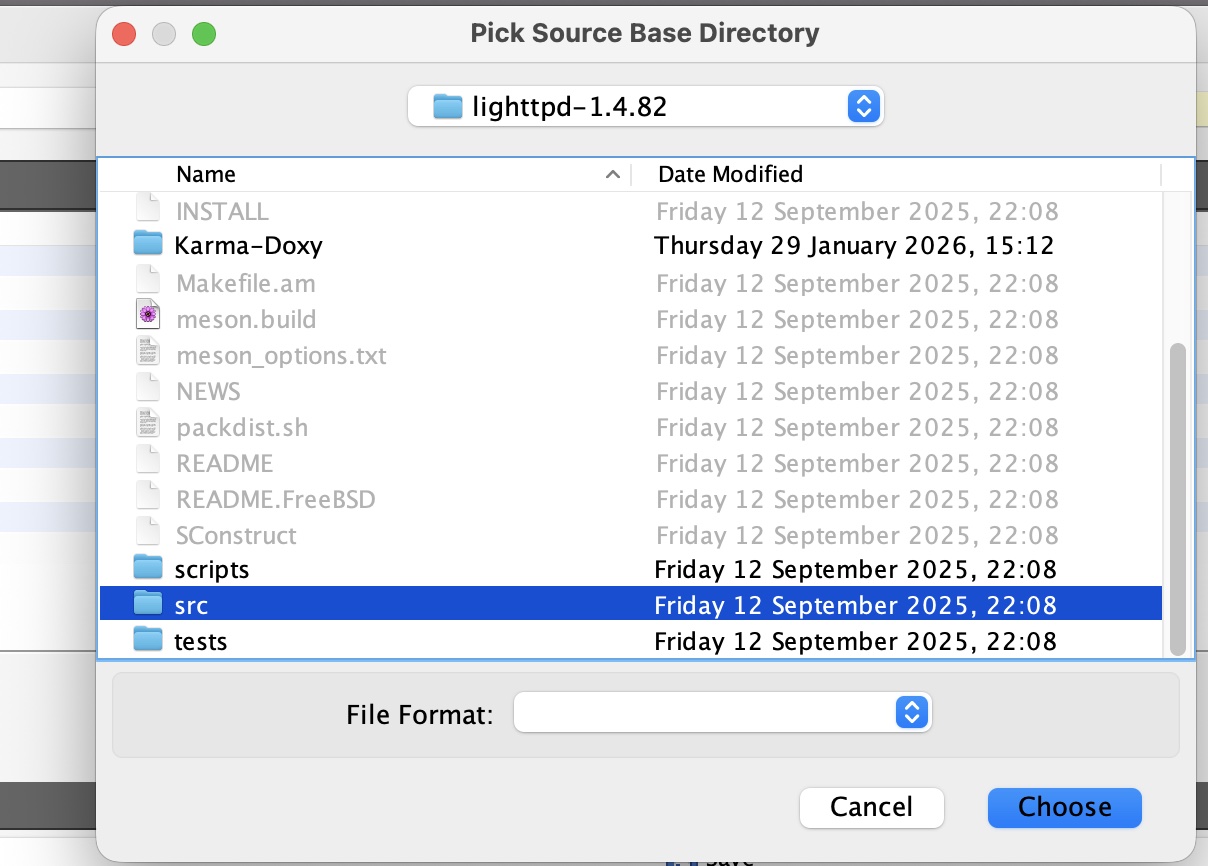

Then we choose the source directory we want to scan:

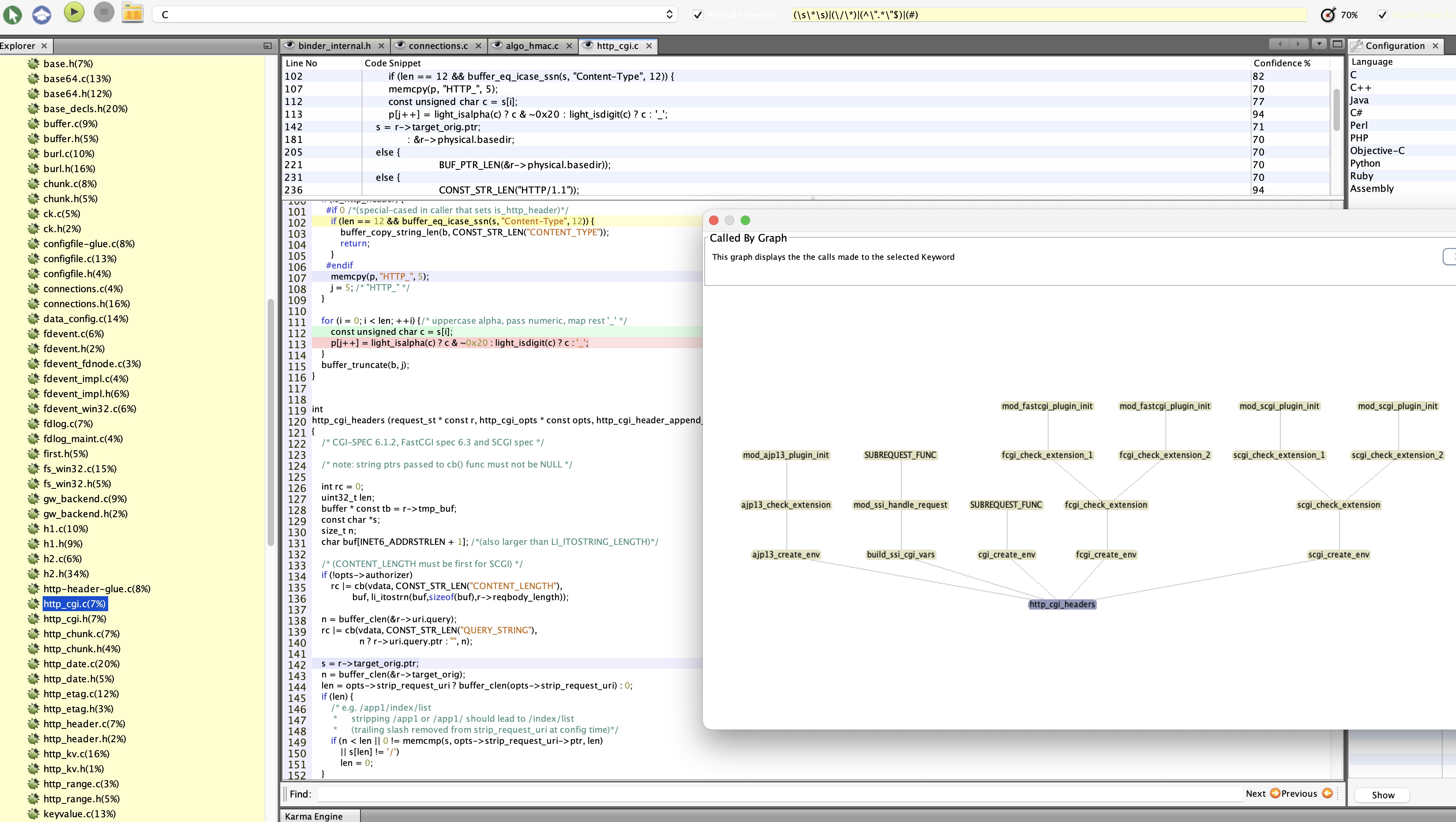

Before we start the analysis, we choose the language we are reviewing (which we can modify in 'Tools' > 'Settings'), we might want to exclude lines that include some strings in which we have no interest. To do this we just type our exclusions in the text box.

After pressing 'Start Analysis' and initiating the scan, the following happens:

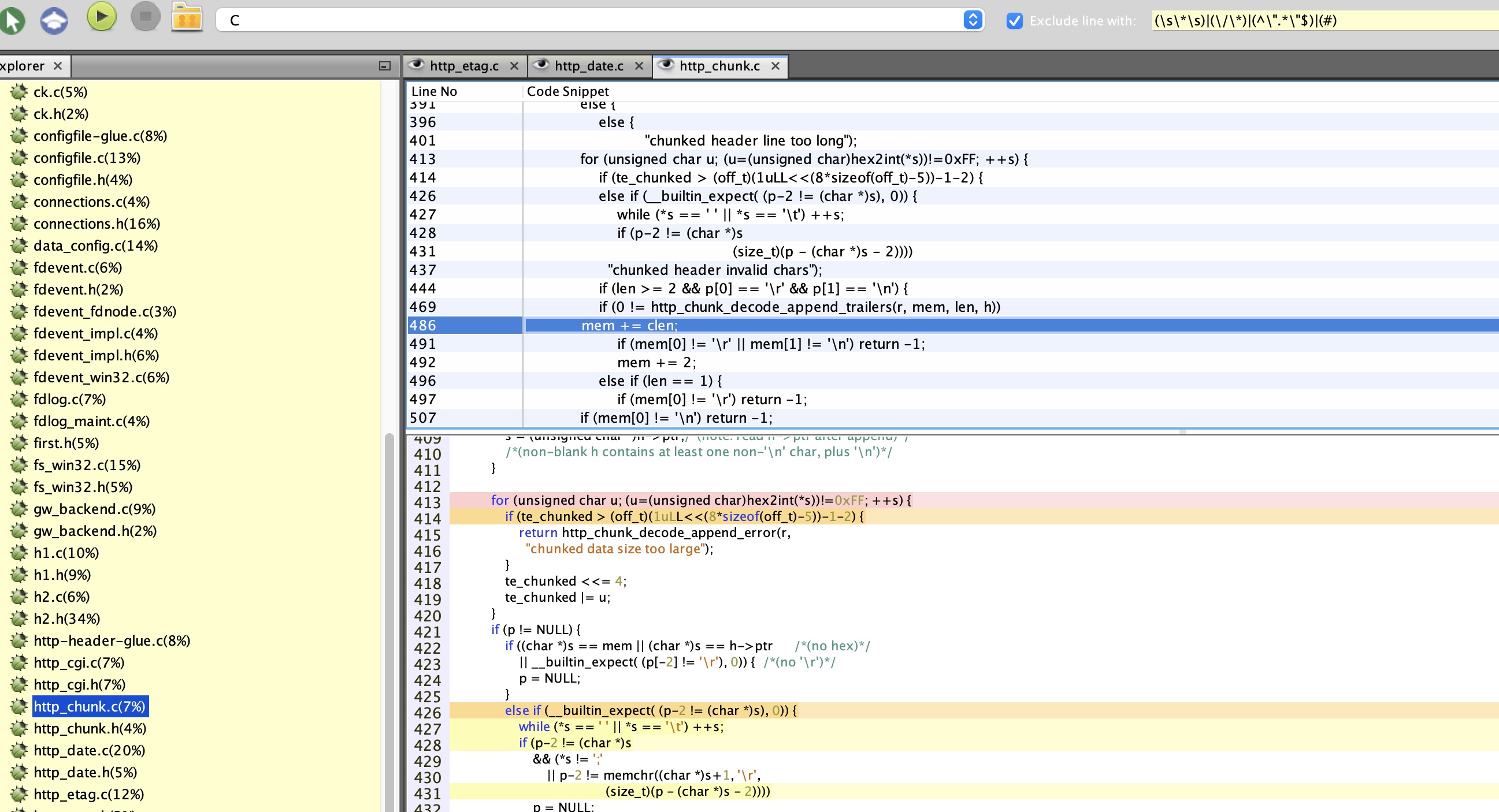

And the output on screen is:

As we can see above, Karma picked lines with interesting functions and variables. This result came without any fine-tuning but purely from training on a number of security patches, which I have found very effective indeed! The top pane can be used for code speed reading as it includes only interesting code.

Below there is a video of the entire process as been done using Karma3.1 Features

Karma features include: inclusion graph, caller graphs, cyclomatic complexity, supervised learning, advanced code search, advanced xml search, comments graph, keyword cloud, bugs graph, backtrace import, karma exchange (you can send trained Karmas and you can import) etc.

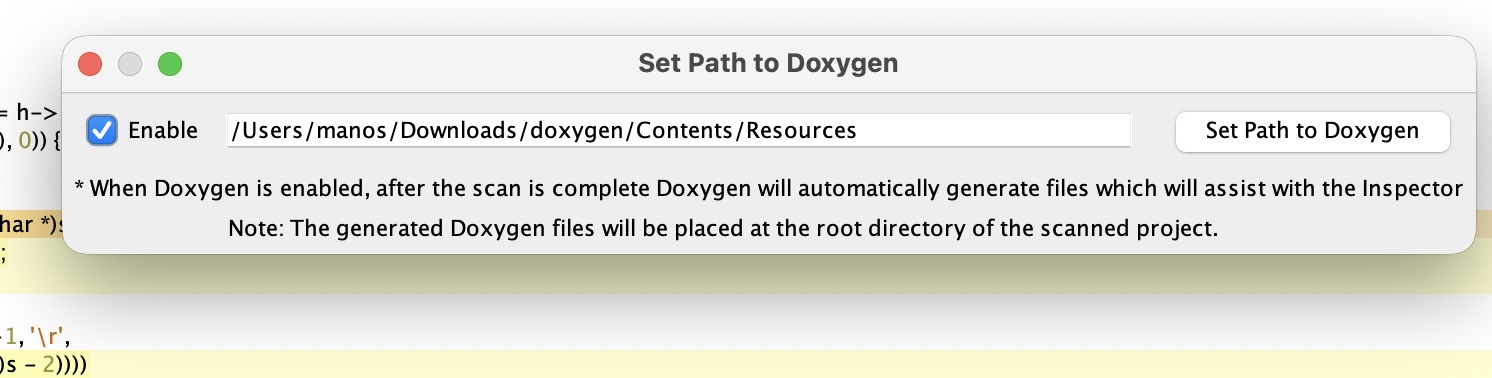

Note, some features require Doxygen so don't forget to set the doxygen directory where you installed it here

Have you found any bugs using Karma? Yes plenty of bugs. Do you have any example bug found with Karma which is public? Yes here there is an example bug found using Karma from 2011. To identify the bug this Karma was used a subset of C specific assigned CVEs which you can download and import to Karma (download it and then go to Karma Exchange and import the zip file). Note that you will see functions been flagged which in many cases don't belong to the core C functions so have a look at the implementation to see how they have been misused (quite common on Kernel bugs)

Here providing Kernel's Karma which is Kernel specific security patches, CVEs which are userland specific patches as training and Learn C which is a subset of security patches based on C patch debian cycle flagged as security patches. Can you use it for any other language other than C? Yes providing here a Java karma and you can make your own for any language as long as you train on patches.

If you want to retrain on patches here there is a zip file containing thousands of linux security Kernel patches, just point Karma's training centre to the directory and retrain your Karma's brain. Note that you can keep training an already existing Karma so if you get more patches you can keep training your linux kernel Karma.Download Karma's binary for MacOS here and get the source code which compiles for OSX, Linux and Windows from here.

For historical reasons providing a download for ParmaHam compiled here and some CVEs to import (note ParmaHam is POC version, last compiled 2009-2010)

4. Works Cited & Bibliography

An Empirical Comparison of Supervised Learning Algorithms.

www.cs.cornell.edu/~caruana/ctp/ct.papers/caruana.icml06.pdf

Bayes, T., & Price, M. (1763). An Essay towards Solving a Problem in the

Doctrine of Chances. http://rstl.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/53/370

MacKay, D. J. Information Theory, Inference and Learning Algorithms. Cambridge

University Press; Sixth Printing 2007 edition (25 Sep 2003).

Webb, A. Statistical pattern recognition. Wiley-Blackwell; 2nd Edition edition (18 July 2002).

Bishop, C. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning. Springer; New Ed edition (1 Feb 2007).

A Comparison of a Naive Bayesian and a Memory-Based Approach

National Centre for Scientific Research “Demokritos”, Annual ACM Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, 2000

Oxford Dictionary: http://www.askoxford.com:80/concise_oed/classify?view=uk

Bugle. http://cipher.org.uk/Bugle/

BinDiff. http://www.zynamics.com/bindiff.html

A Critique of Software Defect Prediction Models

Norman E. Fenton, Member, IEEE Computer Society, and Martin Neil, Member, IEEE Computer Society

N.E. Schneidewind and H. Hoffmann,"An Experiment in Soft- ware Error Data Collection and Analysis

IEEE Trans. Software Eng., vol. 5, no. 3, May 1979.

D. Potier, J.L. Albin, R. Ferreol, A, and Bilodeau, "Experiments with Computer Software Complexity and Reliability,"

Proc. Sixth Int’l Conf. Software Eng., pp. 94-103, 1982.

T. Nakajo, and H. Kume, "A Case History Analysis of Software Error Cause-Effect Relationships,"

IEEE Trans. Software Eng., vol. 17, no. 8, Aug. 1991.

T.M. Khoshgoftaar and J.C. Munson, "Predicting Software Devel- opment Errors Using Complexity Metrics,"

IEEE J Selected Areas in Comm., vol. 8, no. 2, pp. 253-261, 1990.

Automatic Identification of Bug-Introducing Changes

Sunghun Kim, Thomas Zimmermann, Kai Pan, E. James Whitehead, Jr.

D. Cubranic and G. C. Murphy, "Hipikat: Recommending pertinent software development artifacts,"

Proc. of 25th International Conference on Software Engineering (ICSE 2003),

Portland, Oregon, pp. 408-418, 2003.

M. W. Godfrey and L. Zou, "Using Origin Analysis to Detect Merging and Splitting of Source Code Entities,"

IEEE Trans. on Software Engineering, vol. 31, pp. 166- 181, 2005.

A. E. Hassan and R. C. Holt, "The Top Ten List: Dynamic Fault Prediction,"

Proc. of 21st International Conference on Software Maintenance (ICSM 2005),

Budapest, Hungary, pp. 263-272, 2005.

S. Kim, E. J. Whitehead, Jr., and J. Bevan, "Properties of Signature Change Patterns,"

Proc. of 22nd International Conference on Software Maintenance (ICSM 2006), Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2006.

A. Mockus and L. G. Votta, "Identifying Reasons for Software Changes Using Historic Databases,"

Proc. of 16th International Conference on Software Maintenance (ICSM 2000), San Jose, California, USA, pp. 120-130, 2000.

T. J. Ostrand, E. J. Weyuker, and R. M. Bell, "Where the Bugs Are," Proc. of 2004 ACM SIGSOFT International Symposium on Software Testing and Analysis, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, pp. 86 - 96, 2004.

J. !liwerski, T. Zimmermann, and A. Zeller, "When Do Changes Induce Fixes?" Proc. of Int'l Workshop on Mining Software Repositories (MSR 2005), Saint Louis, Missouri, USA, pp. 24-28, 2005.

I. H. Witten and E. Frank, Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques (Second Edition): Morgan Kaufmann, 2005.